Cameroon’s impasse is not only a crisis.

Cameroon at a Crossroads: Learning from the Impasse to Imagine a Shared Future

Yaoundé, December 27, 2025.

Cameroon today stands at a critical crossroads.

The country is not only facing a political or security challenge, but a deeper question about how it understands itself, its history, and its future.

The current impasse did not arise from a single failure or a single actor.

It is the result of interconnected historical choices, governance traditions, internal divisions, fear, and economic strain.

Seen together, these factors form a complex system that cannot be addressed in isolation.

Understanding this system is not about blame. It is about learning, thinking clearly, and creating the mental space for a more courageous and hopeful future.

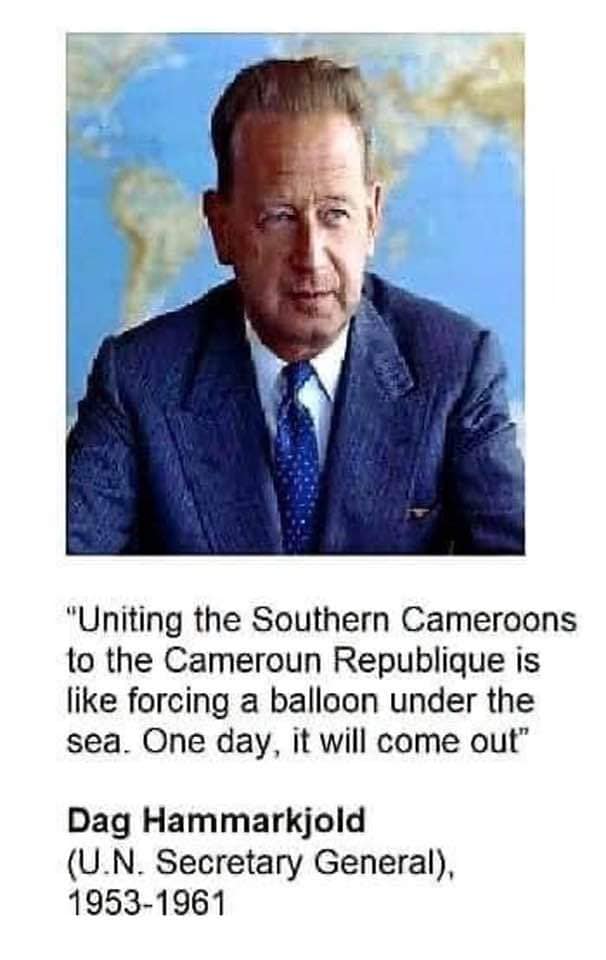

The Unfinished Business of Decolonization and Unification

The roots of the current crisis reach back to the decolonization period.

Southern Cameroonians voted for unification with a sense of hope and responsibility, believing that cooperation between the two historical systems could produce a stronger, fairer state.

With time, however, several of the very leaders who championed unification acknowledged that critical safeguards were missing.

The outcome gradually came to be experienced by many as absorption rather than partnership.

This perception has had lasting consequences.

For some within the Francophone administrative culture, unification became internalized as a completed conquest rather than an ongoing agreement requiring care and balance.

For many Anglophones, it became a story of promises made but not kept.

These contrasting interpretations continue to shape attitudes, behaviours, and expectations today.

Recognizing this divergence is not an act of hostility. It is a necessary step toward mutual understanding.

Governance Traditions and the Question of Everyday Dignity

Unification carried with it an expectation of governance transformation.

There was hope that centralised and coercive administrative practices inherited from colonial rule would give way to a more pluralistic and accommodating approach.

Southern Cameroons was expected to retain meaningful influence over its education system, judicial practice, language use, and productive life.

Instead, many citizens in the Southwest and Northwest experience daily encounters with security, administrative, and judicial institutions that operate almost exclusively in French.

These experiences are not abstract policy debates. They are lived realities that shape how people see the state and their place within it.

Over time, repeated exposure to such encounters has created a quiet but persistent sense of second-class citizenship.

Addressing this is less about legal technicalities and more about restoring everyday dignity.

Internal Anglophone Divisions and the Burden of Fear

The Anglophone experience itself has never been uniform.

Political anxieties between what are now the Northwest and Southwest regions predate the current crisis.

Leaders in the Southwest feared that demographic realities could threaten their heritage and influence within an independent Southern Cameroons.

In response, survival strategies emerged that favoured alignment with central power rather than internal solidarity.

These choices were understandable in their historical context, but they had lasting effects.

They weakened collective bargaining power and deepened mistrust among Anglophones themselves.

This fragmentation made it easier for external actors to manage divisions rather than address shared concerns.

Learning from this history requires honesty without accusation and empathy without denial.

The Rise of Rupture Thinking

The Ambazonian movement reflects a different response to the same historical frustrations.

Drawing heavily from the Anglophones, it interprets decades of failed accommodation as evidence that coexistence is no longer possible.

For its supporters, rupture is not extremism but a conclusion reached through painful experience.

At the same time, many others fear that rupture risks replacing one form of domination with another, or that it forecloses opportunities for reform and coexistence.

These competing fears have hardened positions and reduced space for dialogue.

Understanding them side by side helps reveal that most actors are driven less by hatred than by a desire for safety, dignity, and control over their future.

Fear as a Systemic Constraint

Fear has become one of the most powerful forces shaping Cameroonian politics.

Many believe that open debate is dangerous, that political engagement leads to imprisonment, exile, or worse.

The state’s overwhelming coercive capacity, combined with armed resistance and cycles of retaliation, reinforces this belief.

When fear dominates, people stop listening.

They stop imagining compromise.

They retreat into absolutes.

Even thoughtful analysis is perceived as provocation.

A society governed by fear loses its capacity to learn from itself.

Rebuilding confidence in peaceful expression is, therefore, not a concession to any group.

It is a prerequisite for national learning and renewal.

Human Capital, Economic Life, and the Cost of Uncertainty

One of the quiet tragedies of the crisis is the loss of human energy.

Many skilled Cameroonians now live abroad, disengaged or openly hostile to the system.

Inside the country, prolonged insecurity and uncertainty have disrupted livelihoods, education, and enterprise, especially in the Southwest and Northwest.

Economic life thrives on trust, predictability, and inclusion.

When uncertainty dominates, initiative declines and opportunity narrows.

This reality affects everyone, regardless of political position.

Recognizing this shared cost can help shift thinking away from zero-sum narratives toward collective responsibility.

Learning, Courage, and the Space for Positive Thinking

These intertwined challenges cannot be resolved through denial or force alone.

They require a willingness to learn from history without being trapped by it.

This learning demands hard choices, including the courage to tolerate dissent, to respect diversity in language and law, and to separate political authority from everyday livelihood.

Most importantly, it requires unconditional confidence in Cameroonians themselves.

Confidence that citizens can disagree without violence.

Confidence that institutions can change without collapse.

Confidence that the future does not have to be a continuation of the past.

Cameroon’s impasse is not only a crisis.

It is also an invitation to think differently, to listen more deeply, and to imagine a shared future built on dignity rather than fear.

That possibility begins with learning, and with the courage to believe that a better morning can still be constructed together.

Mba’a Ngembeni Wa Namasso.